We as humans have curious minds, and these curiosities have often led to discoveries that changed the world. All the other times… well, it remains a figment of our memory that is pretty much only good as a conversation starter – “would you like to know what would happen if an astronaut farted in space?”

Nonetheless, for a good laugh or otherwise, let’s see if I can help you out with your thought-provoking curiosity on the effects of passing gas in outer space.

Why do we fart?

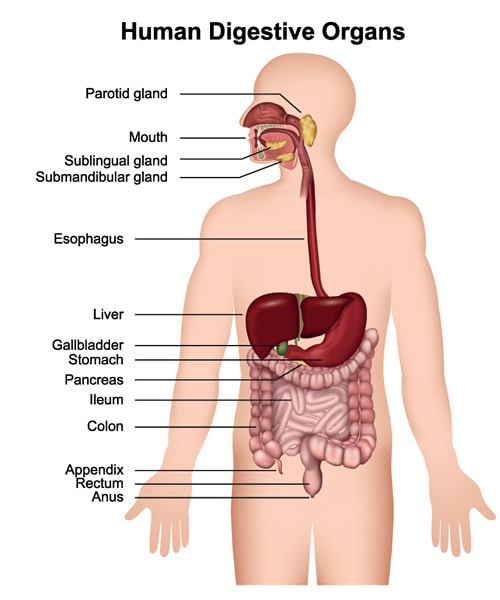

Farting is a human physiological mechanism that reacts to the build-up of gases within the gut, which are generally expelled through the anus as flatulence.

In case you are not familiar, the gut is not the same thing as our stomach. The gut (gastrointestinal tract) is the long tube that encompasses all the organs starting from the mouth to the anus. This includes the mouth, esophagus, stomach, pancreas, liver, gallbladder, small intestine, colon, and rectum.

99% of our bowel gases are composed of five gases, Nitrogen, Oxygen, Carbon Dioxide, Hydrogen, and Methane. These gases are often obtained from three sources: swallowed air, production within the gut, and diffusion from the blood into the gut lumen. (1)

Swallowed Air

Many ways exist for air to make its way into the gut.

Air can be swallowed in the form of gas trapped in food. This includes our healthy habits of eating an apple (~20% gas by volume) or drinking water (a glass of water may result in the ingestion of two times as much air as water).

Air can also be ingested to the gut by just the regular aspiration of air unassociated with eating. For some, this occurs when there is a negative intraesophageal pressure due to the relaxation of the upper esophageal sphincter. (1) If you aren’t familiar with human physiology that’s what I’m here for! The esophagus is the path that delivers our food from the mouth to the stomach. If the upper sphincter (one-way gate) is loose, it means a lot of unwanted substances might get in… Including the air that was meant for the lungs!

What this process would look like from a third-person perspective appears to be the motion of “sucking” instead of swallowing air through the mouth. (1)

Gas Production in the Gut

Gas in the form of Carbon Dioxide can be produced in the gut when gastric or fatty acids react with bicarbonate (part of the mucus that lubricates the walls of the gut), or it can be directly released by intestinal bacteria. (1)

Carbon dioxide might also be produced when we eat foods containing nonabsorbable carbohydrates such as beans, as the organic acids produced by the bacteria during the carbohydrate fermentation reaction are responsible for the generous amount of carbon dioxide excreted. (1)

The unfortunately noxious smell we sometimes observe from a friend after they try to hide their excretions are the handiworks of hydrogen sulfide and skatole, which are trace quantities of volatile metabolites produced by gut bacteria. (1)

Diffusion of Gases from Blood and Lumen

The lumen might sound unfamiliar to some, but it’s actually referring to the hollow passageway that blood flows through!

Diffusion of gases between our blood and the lumen is a net movement down the partial pressure gradient. Nitrogen, Oxygen, and Carbon Dioxide are usually the only three gases with an appreciably high concentration within the blood. But like I mentioned above, since the gut also produces high quantities of carbon dioxide, its pressure would be higher outside the lumen and diffuse into the blood instead.

How are these gases expelled?

The elimination of these gases from the gut can be removed in three ways: convection via eructation and passage per rectum, metabolism by the intestinal, and diffusion into the blood. (1) As we are speaking about passing gas today, we will only be taking a look at convection via eructation and passage per rectum.

This process might be easier to understand if I defined each term separately.

‘Convection’ is the process for the transfer of heat within a substance. It is the root of the common saying: warm air rises, and cooler air drops down.

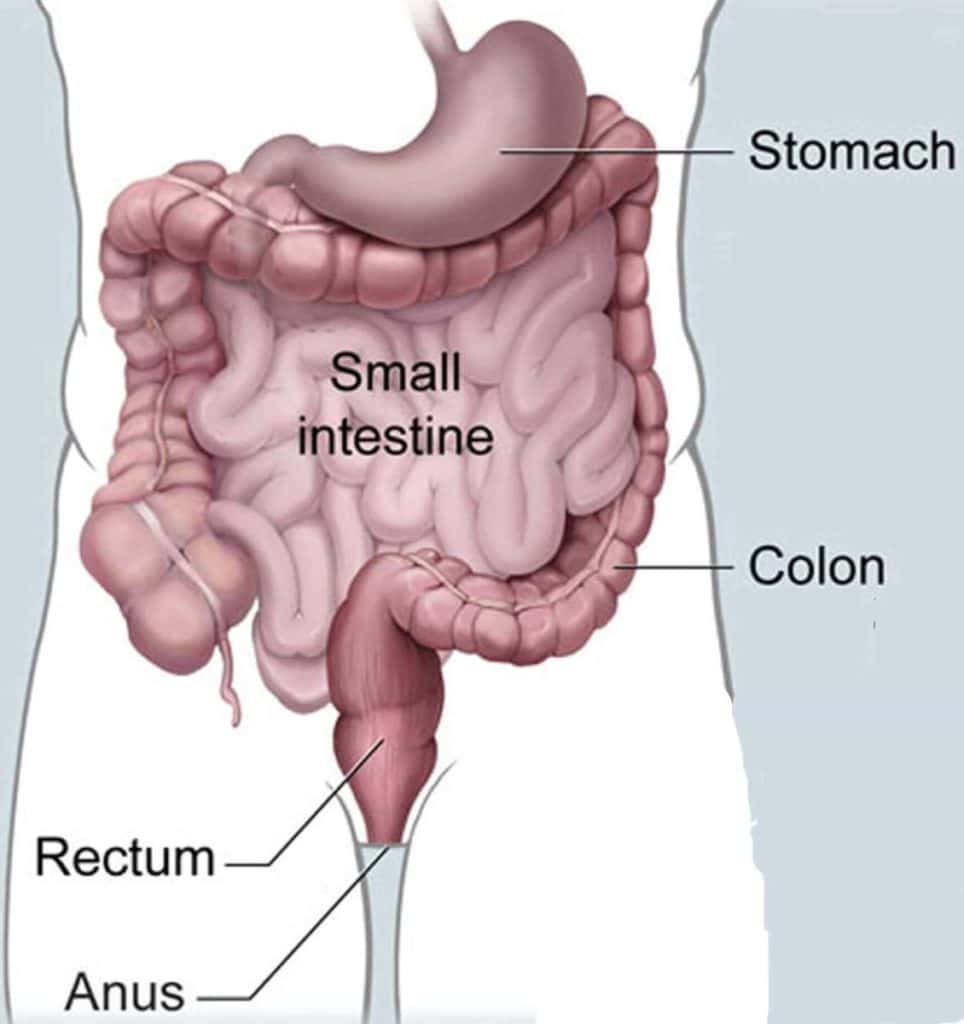

‘Eructation’ indicates the action of belching, while ‘passage per rectum’ refers to movement throughout the rectum – a chamber that stores the waste our body produces until it can be passed out through the anus.

Belch or burp can generally be thought of as the release of gas (fart) through the mouth by the process of convection – the movement of air. This generally occurs due to the action of swallowing excess air. However, most of the air never makes it into the stomach and remains in the esophagus. When the one-way sphincter of the upper esophagus can no longer hold back the increase in air pressure, all the trapped air forces its way out the mouth while vibrating the back of the throat – “BURRPPP”!

Passage per rectum or farting is the buildup of the aforementioned gases in the colon, which can put pressure on the colon wall until your body decides it is time to unleash the discomfort to the world. Often times to avoid causing a scene, we tend to tighten our anal sphincter muscles by clenching our buttocks. But be warned – the longer a fart is held in the higher the pressure, which means the louder it will be. Not to mention holding in farts can cause immediately increased stress levels, pain and discomfort, bloating, indigestion, and heartburn.

Farting is natural! Don’t be embarrassed if it does happen in public, it is a fact of life and it happens to everyone. Although if you do experience excess flatulence, it is advisable to see a doctor and check if your body is functioning to a healthy standard.

Does living in space affect how and how much we fart?

Diet

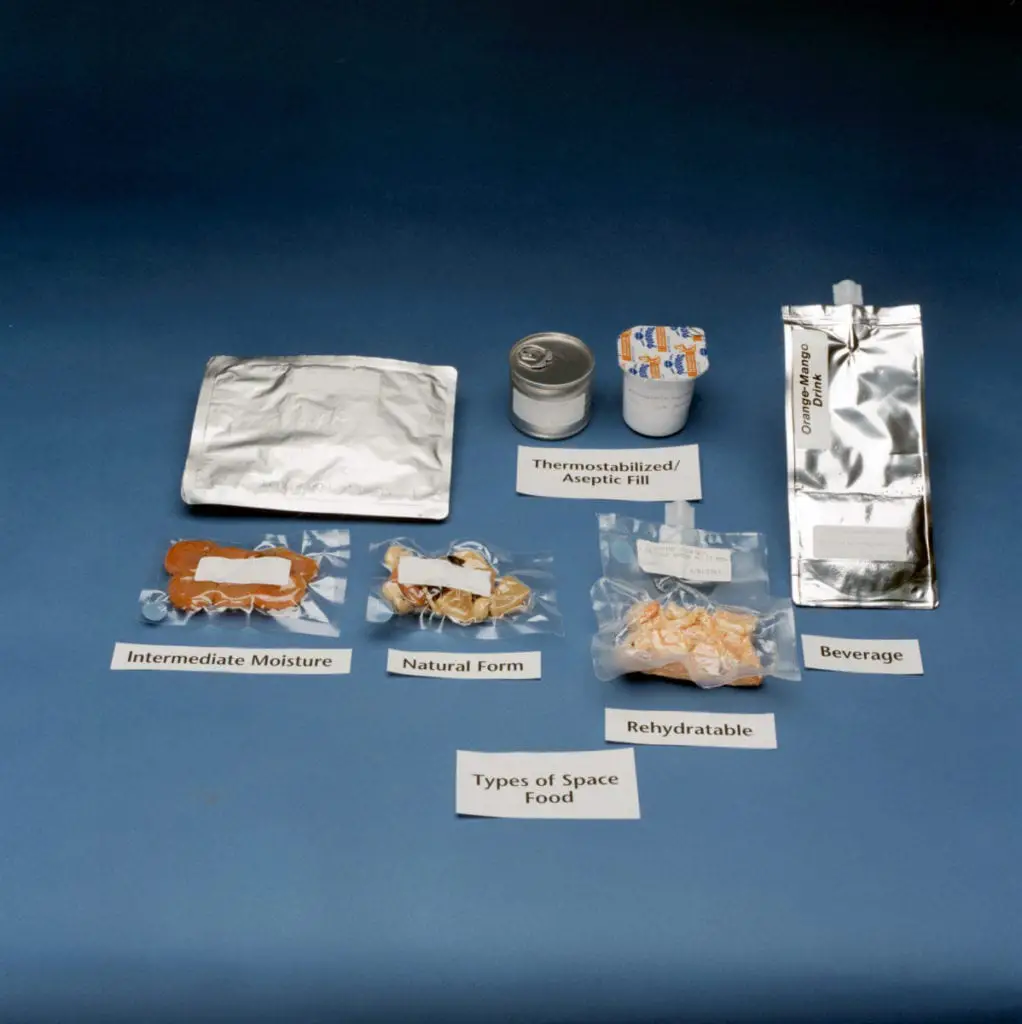

A study (2) conducted by Calloway and Murphy by the name of “Intestinal hydrogen and methane of men fed space diet” compared the effects of different diets on gas formation.

The first group of subjects were fed Gemini-type diets (S), where the composition of the meals was similar to those prepared for the astronauts of the Gemini program. Another group of men received a diet composed of a bland formula (F). The two groups were observed and monitored for 42 days (6 weeks), with breath and rectal gases analyzed during the first and final weeks.

The results of the study varied slightly, but the final result concluded that the Gemini-type diet actually generated more gases than the bland diet, and the volume of gas produced would be larger at reduced spacecraft and suit pressures.

Reduced Pressure

An example of the production of an increased volume of gas at reduced pressure is High-altitude flats expulsion, which is a gastrointestinal syndrome that results from the increased quantities of rectal gas at higher altitudes.

We experience less atmospheric pressure at higher altitudes due to the reduced effect of gravity on air particles. This reduced external pressure makes for a greater urge to expel gas as the pressure buildup within the colon needs to overcome a lower atmospheric pressure exerted on the human body.

To remain consistent with Boyle’s law (pv = k) at a constant temperature, the amount of gas produced would remain constant in mass, but the volume would increase as external pressure drops.

What does an astronaut say?

What did we learn from this study? Well, mission control really has to be careful with what kind of food they send up with the astronauts regarding its fermentable substrates and microflora, as well as the type of environment created inside a spacecraft. In an interview by Gizmodo with Mike Massimino about his last two trips into space to fix the Hubble Space Telescope, Massimino mentions:

“There’s not as much airflow inside a spacecraft or station as on Earth (for obvious reasons). The airflow needs to be introduced to get rid of contaminants and different types of gases like carbon dioxide. The nice thing to do is to go to the restroom where there’s more ventilation to take the odor away. Similar to Earth, if you have to do it (fart), either you do it in private or get people mad at you. That’s the kind of thing that can lead to crew disharmony.”

What happens if you farted in your spacesuit or spacecraft?

Farting in a Spacesuit

The heavy and bulky spacesuits that astronauts wear when leaving the International Space Station to fix equipment or for spacewalks are actually more complex than they seem. Under the big outer layer, astronauts wear another piece of clothing (undersuit) that covers the entire body except for the head, and around the neck remains a distinct layered seal for the helmet.

Therefore, if you farted within your spacesuit the next time you visit space, you would fortunately not be able to smell it, but unfortunately, your body will be soaking it all in… That is until you come back into a pressurized environment and unleash the horror upon everyone near you.

Farting in a Spacecraft

Like Mike Massimino mentions, there is not much airflow within a spacecraft, and this lack of ventilation will actually exaggerate the fart smell as the air gets recycled.

Aboard the International Space Station, by-products of human metabolism such as methane from flatulence or ammonia from sweating are removed by the Trace Contaminant Control System (TCCS).

The black char remains that we usually see from burnt firewood is actually consists mostly of carbon, but it also contains traces of other volatile compounds. The industrial process of producing charcoal allows it to remain purely carbon through the use of a vacuum chamber. These purified industrial-grade charcoals are named activated carbon.

These activated charcoal/carbon filters are excellent sorbents for the removal of airborne organic contaminants due to their small, low-volume pores that increase the surface area available for adsorption or chemical reactions.

On the ISS, expendable carbon beds with activated carbon are used, however, certain contaminants may bleed off the sorbent bed or breakthrough early, so a portion of this waste is routed through a catalytic toxic burner. This toxic burner uses a 0.5% palladium on aluminum as a catalyst, as palladium is the most effective metal for methane oxidation (from farts).

Other gases that are released along with methane as part of flatulence include oxygen, hydrogen, nitrogen, and carbon dioxide.

Although it might seem a little stomach-churning, the oxygen can be recycled for astronauts to breathe while the nitrogen is utilized to maintain total pressure within the cabin. Hydrogen on the other hand can be utilized by fuel cells to produce electricity, however, excess hydrogen must not be stored due to its flammability and is vented out into space. The carbon dioxide released as a part of flatulence and exhaling is removed from the cabin air by the carbon dioxide removal system (CDRA), through which the CO2 is dumped overboard.

Can you propel yourself in space by farting?

With a single fart, it is very hard and near impossible to propel yourself through space.

The function of a propulsion system is to provide thrust and thrust must be directed towards one single direction in order to provide movement. As Newton’s third law of motion states, for every action, there is an equal and opposite re-action.

Unfortunately, with our body acting as the propulsion system, the anatomy at the anus does not enable us to concentrate the gases in one concerted direction; it is rather released in all directions.

But let’s say in a perfect world we can concentrate our farts in a single direction, what would happen then? Thankfully, a Reddit user by the name VeryLittle finished some thought-provoking calculations for us.

Assuming the average person produces roughly one liter of flatulence a day, composed of hydrogen, carbon dioxide, methane, nitrogen, and oxygen, that comes out to 0.5g of gases every day for a normal person.

If the fart leaves the butthole at about 1 m/s (not entirely unreasonable), the flatulence of an entire day would amount to a momentum equal to 0.0005 kg m/s, which is only about 1000x faster than hair grows.

“If an astronaut in space farted every day, it would take 10,000 years for him to get up to a normal highway speed.”

Who was the first person to fart on the moon?

John Young, on his twelve-day Apollo 16 mission spent 71 hours on the surface of the moon, during which Commander Young had a hilarious exchange with the Lunar Module Pilot Charlie Duke, to which he didn’t realize was broadcasted on NASA’s public channel. (This conversation can be seen and heard in the video below)

The increase of citrus fruits within the diet of the Apollo 16 crew that gave Young the “acid stomach” was largely in response to the experiences of the Apollo 15 mission, where the mission’s crew developed irregular heartbeats, which was later diagnosed as potassium deficiency that ended up with mission control sending with Young potassium-fortified fruit drinks and a lot of orange juice. (Inverse)

References

- Levitt, M. D., & Bond, J. H. (1980). Flatulence. Annual Review of Medicine, 31(1), 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.me.31.020180.001015

- Calloway, D. H., & Murphy, E. L. (1969). Intestinal hydrogen and methane of men fed space diet. Life sciences and space research, 7, 102–109.